- Home

- Larry Buhl

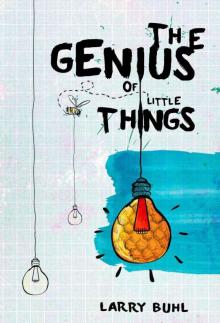

The Genius of Little Things

The Genius of Little Things Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

FIRST EDITION, January 2013

Copyright (c) 2012 by Larry Buhl

All rights reserved

Cover design by Damonza

Interior layout: www.formatting4U.com

www.larrybuhlbooks.com

Printed in the United States of America

An original publication of Beso Books

For the castaways

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ALSO BY LARRY

ONE

August 26. Class journal number one is a list of dumb things people say:

· Smile, it’s not so bad. Maybe it is that bad. And why are they imposing their good mood on someone else? Today, the woman who registered me for classes, and my biology II teacher, told me to smile. Both times, I thought I already was smiling.

· How are you? People want me to answer “fine.” They don’t care if the pollen count is high and my sinuses are inflamed. I informed my case manager of those issues at my phone check-in last week. He responded as he usually does: “Awesome, awesome!”

· Are we having fun yet? If you have to ask…

· Let go and let God. Let God do what? Vagueness is irksome.

· God bless you. When people sneeze, I respond with “Gesundheit,” unless they don’t cover their mouths, in which case I retreat quickly. In one of my seventh grade extra credit history papers, I wrote that gesundheit was originally used to prevent the sneezer from being invaded by evil spirits. In the future, I may respond this way to mess with superstitious sneezers. I will say, in a cryptic voice, “This is how it begins.”

**

It was getting late. I had spent too long on my class journal and had made no progress on my Caltech admissions essays. I was applying through early admissions, a process that was like choosing only one bride when the bride has the option of rejecting you. One might ask, “Why not skip early admissions and apply during the regular deadline?” The answer was to set a course for my future as early as possible. Knowing where I would be attending college by December 15th, rather than March, or later, would eliminate months of uncertainty. I had enough uncertainty in the Foster-go-Round, AKA Nevada Department of Child and Family Services, and earlier, with my biological mother, or BiMo.

I should not bring up my BiMo again, nor will I delve into the circumstances surrounding her death.

But I’ll offer this advice. People with severe allergies to shellfish and eggs should not leave their EpiPen at home when they go to a Thai restaurant and request something with shellfish and eggs. If they ignore this advice, when they experience the inevitable anaphylaxis, they should not leave the restaurant and stagger along an empty sidewalk until they collapse. As the saying goes, if I can save one life, it’s worth it.

The first Caltech essay prompt—Tell us anything you think we should know about you—was maddeningly ambiguous. My efforts contained gems like my opening paragraph.

The gazelle, when separated from the herd, is in a precarious situation. However, should he survive, he will grow stronger and wiser for the next onslaught. I am that gazelle, surviving and growing.

You are that admissions committee, laughing and hurling.

I concentrated on the second essay prompt. Communities we are born into, those we make, and those we fall into by accident, influence us and shape us. Describe a defining community in your life and what it means to you.

Even though many of my extra credit essays over the years turned out all right, I’m not much of a writer. Composing an essay about cyclonic separation, for example, was a breeze—and I don’t think this was a pun, intended or otherwise—compared to summing up my life experience while trying to sound upbeat about the whole thing.

Humans have much to learn from honeybees. Their society is a well-run machine, not unlike the most effective human communities. The ongoing colony collapse disorder that is now devastating bee colonies shows the limits of sociability. It is theorized that, because the bees know they are sick, they fly off together in a mass die-off. Living together. Dying together. This is why I want to call Caltech home.

I had a brain fart. This is not a medical term. It means that I couldn’t think clearly, temporarily. I required the assistance of Cap’n Crunch. I always disliked how products bastardized the spelling of real words. However, that didn’t stop me from consuming something that would have more accurately been called Captain Crunch, or Crunchy Sugary Cereal Squares. Whatever. Product naming was not the contribution I would make to society.

In the pantry, affixed to my cereal box, was a yellow post-it note. This has a lot of sugar. I left the note on the box. I had been considering better cereal choices, even though good nutrition was always more expensive. Now that someone I hardly knew was pestering me to eat healthier, I wanted to keep consuming crap.

Walking back from the kitchen, I briefly peeked into my FoFa’s office. FoFa is a term I use for foster father. It is shorter than foster father, although I realize I have used many words to explain this. FoHo means foster home. FoPa means foster parent. FoMo is foster mother.

Anyway, his real name was Carl.

Carl worked as a part-time professor of computer science at the University of Nevada in Las Vegas. He alluded to previously owning some kind of technology business in California. That, and the fact he liked cars and old clocks, and had traveled extensively, were all I knew about him.

Carl hunched over a desk covered with tiny, saw-like pieces of metal, an old rotor, screws, bezels, and glass. On the far wall were display shelves containing several dozen ancient clocks in various states of disrepair. I lingered a nanosecond too long. He looked up and raised his glasses. “There’s Carl, getting his clock cleaned again,” he said.

I wanted to respond, but nothing came to mind. It was odd hearing someone speak of himself in the third person. Later that night, I learned that cleaning someone’s clock was a euphemism for giving that person a beating. In the past, I was often perplexed by euphemisms and other clever English phrases. My teacher for tenth grade English told us to “avoid clichés like the plague.” She thought that was witty, but I didn’t get it, until someone explained that like the plague was a cliché and that my teacher had made some kind of double cliché. Lately I have reached a cease-fire in my battle with metaphors, similes, and other figures of speech so they are no longer albatrosses around my neck.

Carl was cleaning a clock, literally, but not getting it cleaned. I didn’t challenge him on this distinction. I didn’t ask him about his clocks, and I didn’t expect him to go into detail about the d

ifficulty of replacing rotors. But he did. I listened.

One thing did impress me. Carl said he liked old clocks because they were well engineered and that modern electronics were built to be disposable. I kept an overstuffed Box o’ Crap under my bed because I hated throwing things away, so I appreciated Carl’s point about hanging on to things, long before he stopped making it.

Then he asked about my first day of school.

“It could have been worse,” I said.

He laughed, although I didn’t see what was funny. He inquired about my classes, so I provided my new schedule—calculus, applied physics, German IV, biology II, and English lit. I omitted the Creative Soul class because it would require too much explaining.

He wanted to know what topics would be covered in physics.

“Quantum chromodynamics.” The teacher hadn’t given us a syllabus yet. Quantum chromodynamics was the first physics phrase that came into my head. It was something I read in Scientific American magazine. I don’t know why I didn’t tell Carl the truth.

“I wish I could help you out,” he said. “If you need to know a thing or two about software design, I can help.”

My Cap’n Crunch was becoming a pond of tan sugar slurry. I thanked Carl for his offer. I took my bowl back to the kitchen to start over. I stared out the kitchen window and waited for the milk to transform the cereal into the perfect consistency, Cap’n Crunch al dente, while considering my approach to Caltech’s “community” essay. The blinds in the neighbor’s kitchen window pinched apart. I saw an eye. The blinds closed.

I must have lost track of time, because by the time I headed back to my room with my new bowl of cereal, Janet, my FoMo, had materialized in the living room. She was watching a TV show about convicted killers. The announcer said one murderer had “turned to the Bible to help him in his new career as a talk show host.”

Janet snorted. “Good luck.” At first, I thought she was talking to me, but I quickly realized she was making a crack about the killer. She pressed pause and the screen froze on the convict making a pucker face in front of a Bible.

“How was the first day of school?” I noticed Janet and Carl often asked the same questions separately. I wished they would be in the same room at the same time so I could avoid redundancy. I stopped next to an enormous Indonesian cabinet and told her nothing terrible had happened.

She laughed. “No bombs went off?”

I assured her no bombs had exploded. I didn’t know what was funny about bombs. I wondered whether there had been bomb threats at Firebird High in the past. I made a mental note to research that.

She started talking about her day. After a minute, it still wasn’t clear what her job was. I narrowed it down to something sales-related. My small talk session with Carl hadn’t gone as well as I had hoped, so I tried to be more proactive in chitchatting with Janet. “The bees are still dying,” I said.

“Whose bees?”

I explained colony collapse syndrome, in which honeybees were leaving their hives and dying by the billions. The latest research showed that the die-off could be caused by anything from an undiscovered fungus to cell phone signals that mess up their internal radar. I segued into an explanation of why bees were so important. For the record, they pollinate a huge variety of crops. Take away the bees and you take away up to one third of the human diet, from almonds to zucchini.

“Guess we’ll have to live on granola bars pretty soon,” she laughed.

I was silent. I could have pointed out that some granola bars have almonds, but I chose not to.

“Speaking of food, we need to have dinner together,” she said.

We needed to?

I told her I worked at my catering job four nights a week, and that I had to prepare for my Caltech application.

“Aren’t you the busy one?” Her tone indicated this was a statement borne of annoyance, rather than a question.

I said Friday would be all right.

“That wasn’t so hard. I’ll make something with almonds or zucchini, before the bees go extinct.” She laughed. She was doing a lot of laughing about serious subjects. But that was better than yelling and throwing a breast pump for no reason. One of my past FoMos did that.

I took my bowl of Cap’n no-longer-Crunch to the kitchen, hurled it down the drain, and gave up. I gave up on the essays, too. I spent the rest of the evening culling some useless items from my Box o’ Crap.

My Box o’ Crap was a fairly ornate wooden box, about a foot by two feet, and eight inches deep. My BiMo gave it to me when I was ten. I’m sorry to bring up my BiMo again.

**

August 27. Things in my Box o’ Crap:

· A ancient tin of Altoids.

· Programs from all of my science fairs.

· A name tag from a horrible supermarket job.

· Birthday cards from Nevada Department of Family Services.

· Photocopied Christmas letters from biological grandmother, supposedly written by her cat.

· Every letter from Family Services informing me of a transfer to a new FoHo.

· A movie ticket stub, from The Pursuit of Happyness. It was an okay movie, but it bothered me that they misspelled happiness on purpose.

· My BiMo’s unmarked CDs of some of her favorite songs.

**

Sometime around 2 a.m., I remembered I had to work on Friday, so I wouldn’t be able to have dinner with Carl and Janet. And I was scheduled for Saturday and Sunday evening shifts as well. I got up and wrote a note to that effect on the refrigerator white board. As much as I wanted to be accommodating and pleasant, I didn’t want to rearrange my schedule for a FoPa dinner. It was nice of them to offer, but I assumed my case manager put them up to it.

I could imagine the conversation.

Case manager: “Do something for your new foster kid so he doesn’t become a prostitute or drug addict.”

Janet: “Is that likely?”

Case manager: “Happens all the time. Many end up dead.”

Janet: “Oh dear. We should make dinner.”

Case manager: “Awesome, awesome! And keep asking about his school.”

Carl: “We will! And I’ll talk about old clocks!”

I hoped they would forget about dinner. FoPas and biological parents made a lot of promises. By the time they were ready to follow through on any of them, it was usually too late.

TWO

A room with a locking door in a quiet house was all I needed. That’s what Carl and Janet offered. It was a very nice house in an older subdivision, which meant it was built at least a decade ago. Bordering this subdivision was a megastore, a strip mall with a pharmacy, a strip mall with a gas station, and a dusty patch awaiting a chain store. All of these stores were in walking distance.

On the day I moved in, they took me on a tour of the house. They spent more than five minutes showing off their dining table, a heavy, primitive carved wood piece that looked like it belonged in the jungle. Actually, it was made in the jungle. They had it shipped from a village in rural Thailand. I appreciated them taking the time to show me everything. But I received their implicit message. Don’t mess up our beautiful stuff.

Just before the Foster-go-Round transferred me to Carl and Janet’s house, I submitted an application for emancipation. The emancipation process would take four months under the best of circumstances. With the state cutbacks, the system was working even slower than usual. I anticipated that my hearing would be Thanksgiving at the earliest. After that, it would be another month until I was cut loose from the system.

I didn’t bring up the issue of emancipation to Carl and Janet. I assumed my case manager had informed them. Either way, they didn’t need to be involved with the process until the hearing. All I needed to do was stay out of their hair.

My plan required money for an apartment, plus tuition and living expenses for Caltech. There was no guarantee I would receive enough financial aid. That meant I needed to boost my earning potential, stat. The crummiest

bachelor apartment in the vicinity of Firebird High would be at least $400 a month. After seven jobs in two years and over two-dozen tutees, I managed to save only $10,588.

Unfortunately my hours at my latest job were dwindling, and the owner, Mr. Ferguson, had cut our already paltry wages. All catering businesses in Las Vegas were in a slump, but Covenant Catering was in dire shape.

It didn’t help that Mr. Ferguson had been turning away business due to his religious beliefs. He was a devout, newly-converted Mormon who was making up for his “first forty-five years in the spiritual wilderness” by going completely overboard. He would cater no events with alcohol or caffeine and would not work with organizations that promoted moral depravity. He was also against catering functions that had anything to do with gambling. In Las Vegas. He turned down the chance to cater the grand opening of a dental clinic. He thought x-rays were blasphemous. After only three jobs in a month—two wedding receptions and a small office party—he relented on his no caffeine rule and he saw the light on x-rays. I think that’s a pun and an idiom.

Mr. Ferguson kept reminding me that I was the first employee he had hired outside the “flock,” which meant Mormons. He said this so I would feel even more grateful for the job. In the interview I told him I had thought about Mormonism and I was “looking for answers.” I put it exactly that way so he would hire me, thinking he could convert me.

I like to believe that my culinary skills helped in the hiring decision. I was self-taught. My BiMo was not so much a bad cook as an inconsistent one. I had to read labels carefully whenever she was too lethargic to do so. In her last two years she became increasingly careless about avoiding eggs and shellfish. One time I checked the label of a new protein powder. One of the ingredients was apovitellin. I had not heard of that substance before and I told her to wait until I checked it out. Apovitellin, the Web site said, was derived from the low-density lipoprotein of eggs and could cause even worse reactions in allergic individuals than the egg itself. It could have killed her. She gave the tub of protein to her then-boyfriend and thanked me for being so conscientious. I was eleven, by the way. In her last year, I did most of the cooking for us, at least when she was at home. By doing this, I saved her life. Or, rather, I prolonged it a bit.

The Genius of Little Things

The Genius of Little Things